Ian Dapot

Think Tank

AIGA Nashville, 2009

Original presentation for AIGA Nashville Think Tank conference

I should start by giving you a little background about myself and my inspiration for this talk. I was thinking a little while ago that every kid who picks up an electric guitar dreams of being Jimmy Page. And following that line of thinking every kid who picks up a mouse in design school dreams of being a design super star.

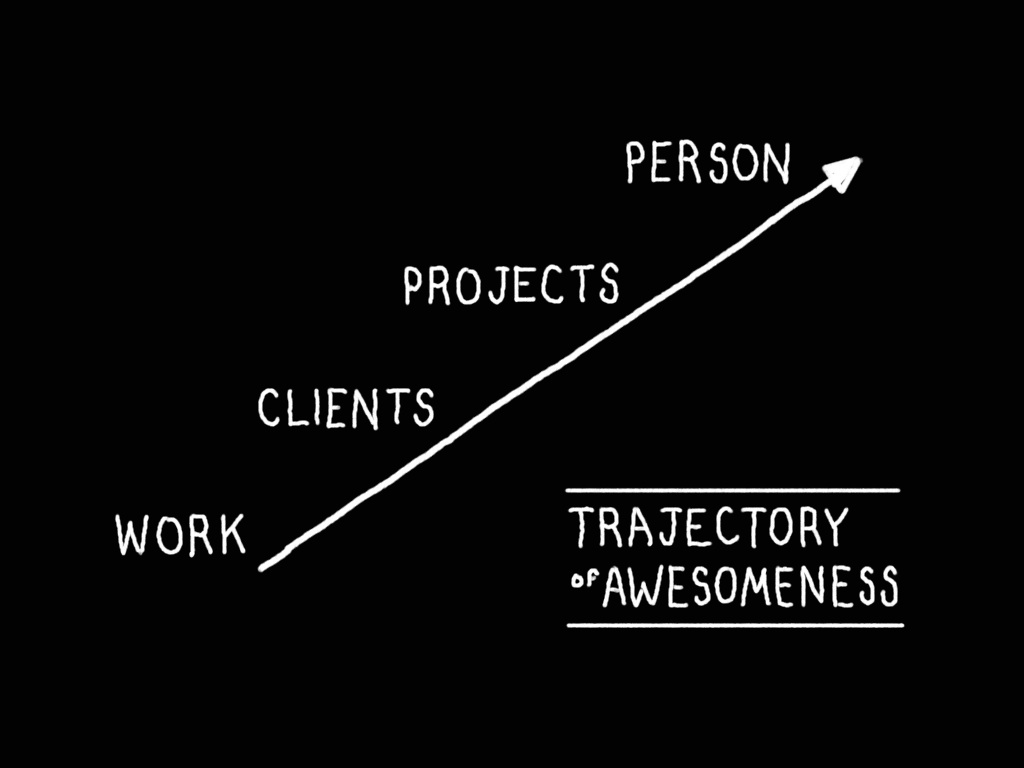

Not to underestimate the difficultly and talent required to achieve that sort of status, but the path to stardom is pretty well conceived. Do cool work, get cooler clients, do cooler projects, become a cooler person. It is basically a trajectory of awesomeness. The design profession has even created titles and awards that help indicate relative degrees of awesomeness to the world.

I'm a formally trained designer and am certainly guilty of imagining my own success along this path. That was until I found myself working at IDEO, in an environment where the path looked very different, if there was even a path there at all. It was a highly collaborative working environment, we didn't have titles, and we didn't always engage the kinds of problems I was used to. The process IDEO uses to approach different problems is called Design Thinking, which was a term I was only vaguely familiar with when I joined. I needed to figure out a way to understand my role in this new environment, to understand design thinking as a process, and a way to consider my progress along that other, better understood path at the same time.

And I should probably give you a little warning: I very much took the title of this conference to heart. Based on early conversations with Phillip, I was excited by the prospect of engaging in a discussion about something other than a portfolio review, it seemed like a worthy experiment and decided to hold myself to it.

I would also like to take a moment to thank some friends and colleagues helped me with this presentation:

Devorah Klein

Ryan Jacoby

R. Michael Hendrix

and Lynn Winter

The term "Design Thinking" used in different ways has been around for at least 15 years. A basic definition of Design Thinking is a creative process of inspiration, ideation, and implementation to build ideas into practical solutions that meet the needs and desires of users. It highlights the plan or working hypothesis as an important part of the design process, as applied to different problems. Over the past five years or so, the value of Design Thinking to businesses and public institutions has become an increasingly hot topic. The increased interest has primarily been part of a larger conversation about the importance of innovation to business and paths to pursue it, not necessarily about design per se. Most often Design Thinking has been explained by pointing at successful examples of new products, and services in the marketplace, and discussing the difference in the process by which they were developed.

It's also worth considering that some of the main voices in this discussion are journalists, engineers, and managers, and by contrast the voices of industrial and graphic designers have been in the minority. However, recently a new thread has emerged in this dialogue about the rejection of design thinking by designers, and I thought it would be interesting to consider that thread here, with all of you. It seems that "Design Thinking" has become a polarizing term. Most non-designers are excited to participate because it gives them license to be "creative", to come up with lots of wild options, or to see familiar problems from a new vantage point. While many designers find the term design thinking has a negative connotation that underestimates the importance of making, especially the importance of thinking through doing, by sketching and formal resolution.

To better understand that difference of opinion I would like to explore how designers and clients perceive each other. Some of the responses designers have had to those perceptions, the ways that we have come to define our roles, and what opportunities might be in available to designers if we begin to consider a different set of criteria.

Let's begin by thinking a bit about where design has been, which doesn't necessarily entail a long review of the history of design, but rather giving some consideration to the role of design and designers. One way to do this is to propose a basic definition of design in order to consider how that definition might change in the future. Historically design has been considered a downstream or final step in bringing products to market; the final shaping, visualization, or application of a beautiful surface to a fixed concept of what the product will be.

Design has been used to drive sales and create appeal by making new products more aesthetically pleasing and differentiating them from existing options. Or to enhance consumer perception of brands through evocative advertising and communication. In some ways designers have been called upon by the businesses we serve to provide solutions, and on the whole designers have answered that call with remarkable results, creating visually arresting and often inspiring work. Built into this definition of design is a particular relationship between designers and their clients. And within that relationship are two underlying mindsets that drive the behavior of both parties. Steven Collopy and Richard Bolland have referred to them as Decision and Design attitudes. I would like to spend just a little time considering each viewpoint.

The Decision Mindset is at the core of this traditional relationship, the designer is engaged to give form to fixed ideas provided by their client, and the client is responsible for deciding between the options presented by the designer. There is a presumption in all of this that the client is equipped with the necessary understanding to make informed decisions about the options presented, and has the vocabulary to express their thoughts. In this situation information and knowledge are applied in making the choice, and there is an implicit agreement that creating options (that is to say doing the design) is the easy part of this relationship, and deciding between them is the hard part.

To this end a great deal of thought has been invested into developing processes to make rational decisions. Most business school programs are built to provide graduates with analytic techniques for deciding between options. You could consider game theory as it has been applied to economics as another way to explore the choices people make. Kahnamen and Tsversky, the only Psychologists to ever receive a Nobel Prize, were recognized for Prospect Theory, and their work to understand how people decide between options that involve financial risk. So there is obviously a high level of interest in how people make decisions, but considerably less attention seems to be paid to what it takes to develop the options themselves.

By contrast the Design Mindset assumes that it is difficult to to create good new alternatives to existing products, but once you have developed a good design the decision about which path to pursue becomes relatively easy. To designers the value of good design is self evident. The hardest work has been done during the design phase. Knowledge and information have been applied to lots of little decisions over time, to arrive at a single option that makes the most sense, as opposed to making one big decision at the end.

Rather than being entirely analytic or rational, the design mindset is observational, intuitive, and experiential. It can be very opaque to an outside observer, and not much energy has been put into making it less so.

I think it is fair to say, that consciously or not, the majority of designers form relationships with clients that align with the Decision Mindset. And one of the ways designers have responded to the limitations of their role in this relationship has been to develop separate criteria to judge and express the value of design in their own terms. Feeling under-valued as contributors, thinkers, and participants through relative isolation at the end of the process, designers essentially began having a conversation between themselves about the things they valued. We basically retreated to a more comfortable conversation. (I also think this is probably natural response.) But in doing so we created more and more refined expressions of style and technique, and a more refined vocabulary to describe them, making the gap between designers and decision makers even more challenging to bridge.

I don't think that designers are alone in this behavior, most highly refined systems of communication, like painting, film, and literature for example, all contain some level of self reflexivity. Practitioners leave clues or messages to other experts about their intentions or allegiances; the structure of a page indicates an affinity to a particular school of thought; a choice of typeface homage to an aesthetic movement or nationality. Almost all of which is lost on the primary audience for the design in question, who will probably just respond that text is hard to read, or that they would have preferred the packaging in a different color or something. It's something most of us have experienced.

This is how most disciplines evolve, but most models of refinement ultimately reach some point of diminishing return. The more evolved the design field becomes, the smaller the increments of improvement, or step changes will be. Which means that getting better gets harder, and the ability of one design solution to stand out from any another becomes increasingly difficult. Bad design will still be easy to see, but good design will be harder to notice, and great design could get lost in the noise. This compounds the potential for problems in communication between designers and clients, because clients will be unable to discern the small differences in the options presented to them, and therefore perceive even less value in the service offered.

This is only worsened if you believe that there's nothing new, or everything out there has already been done, then not only does your work have trouble standing out in an increasingly sophisticated and refined field but you could be recycling some other designers great solution anyway.

This difference in perspective between the decision and design mindsets, and the response of designers creates several potential problems.

First people don't tend to value things that they believe are easy to achieve, and they don't like to pay for, or participate in things they don't value. There is also the problem that designers and their clients aren't using the same vocabulary and criteria to evaluate options. Where a client might consider an option in terms of its "distance to dollars" a designer might be prioritizing the unique experience it would offer users.

Furthermore having conversations where you are either unfamiliar, or uncomfortable with the vocabulary can create obvious tension. It's usually unacceptable to say "I don't know" or "I don't understand" in most business settings, and people will sometimes dismiss ideas out of hand to save face rather than admitting they don't get something. I would venture to say that designers and their clients are equally likely to engage in these behaviors. Designers are often unwilling to learn about the operating constraints of different businesses, and non-designers are unwilling to accept observation and experience in lieu of analysis. Either way the Decision Making mindset is still the predominant path to market for most companies.

The adoption of separate criteria to evaluate design underscores a tendency of designers focus on the depth of their skills in a particular discipline. It's a classic case of being unable to see the forest for the trees. And indicates to some extent that designers are considering the advancement of their skills outside of any larger context, or within an extremely narrow one. It's easy to do.

Bruce Nussbaum recently wrote that the professional engineers, scientists and mathematicians who generate inventions, may be the enemies of innovation. At first it seems a little counter intuitive, that people who are good at generating new inventions would make poor innovators, but there is an important difference between invention and innovation. Invention is about new technology and innovation is about the use or social application of technology in context. Basically, engineers, scientists and mathematicians are too focused on the details of the inventions themselves and not the use of the invention in the world. Use isn't a part of their culture. They have a tendency to get excited about the intrinsic coolness of the thing they made and not about what needs or desires it might fulfill.

Which got me to thinking, are Designers the enemy of design? Are designers just as focused on the intrinsic coolness of the things we make, and not about what they might do in the world? I think a new or emerging definition of design is likely account for the social application of disciplinary skills in context and not just on the acquisition or refinement of the skills themselves.

So as the application of design becomes increasingly important, designers will need to connect to a broader context in order to remain relevant. Simply put, clients will measure graphic designers by their breadth as much as their depth, if they haven't begun to do so already. And by breadth I don't mean that you work in both print and web, or that depth means you know every key command in AfterEffects. Depth in your discipline will continue to be critical, but the extent to which you are able to perceive and engage with the world around you, and outside of your disciplinary practice will become more important.

One suggested approach to a engage in a broader context is to develop a post-disciplinary practice. To do away with traditional disciplinary boundaries as an approach to problem solving. I personally struggle with this, maybe I just like rules, who knows. But the stated evidence for the value of post-disciplinary practice is usually collaboration between individuals with a disciplinary foundation. But to use that evidence as an argument to abandon disciplines all together is a difficult leap for me to make.

Personally I have a great deal of pride in my chosen discipline, I like making things, I like typography, I like to draw, and to think about the way things work together. And over time the accumulated experience of practicing my discipline has helped me to understand how I think, and importantly has helped me to understand ways to engage in non-design problems as well. I work in a highly collaborative environment, with people from many disciplines, and we create outcomes that we could not have alone. But I don't believe that negates the value of viewing the world through disciplinary eyes.

So a post-disciplinary life isn't right for me; even if I didn't have the title Graphic Designer I would still be driven to create things, and would still seek ways to engage with the world in the same way.

I think what drew me to design in the first place was people. Every project I began was an opportunity to meet a new client, understand a new business, and engage a new audience. All of those activities required a set of social skills, and enough understanding of the "humanities" and "business" to form relationships with my clients and understand their broader goals, before I could begin any work that could rightly be considered graphic design.

It was initially invisible to me, I thought I was there to make cool stuff, but all of those social activities have become an increasingly important aspect of what I do. Particularly the aspects of engaging with the social context of the problem, more often than not understanding the context and audience will define the success of my engagement in terms that are not traditionally within the vocabulary of design. A new role for designers will need to incorporate these social skills, and the ability to account for context.

It might be helpful just to mention some of the problems design is engaging right now. Based on my experience alone, which is admittedly not a very scientific sample, there are opportunities to shape the future of some of the most important issues of our time, finances, healthcare delivery, and charitable giving, as well as more traditional areas of engagement like fashion, sports, and media. Designers are engaging in the earliest aspects of problem solving, shaping strategy through asking questions, and by bringing an informed perspective about people to the table.

In order to do this, and feel comfortable in the conversation, I have needed to learn about the clients I have worked with, their businesses, capabilities and limitations, as well as the specific vocabulary that they use to describe what they do. In return I've had to educate my clients about what I do, my capabilities and limitations and share my vocabulary with them in order to make them feel comfortable too. I had to open up to admitting when I didn't know something, and ask questions, a lot of questions.

A little while ago I had the opportunity to work with a large pharmaceutical company. They had recently launched a new drug for children onto the market and sales were poor. Initially you might think that they would have asked a designer for a new packaging solution, positioning, or messaging to boost product sales. But to their credit they realized that the drug hadn't performed badly because of any of formal design solution they had selected. The problem was deeper. They had made multiple decisions during the process of developing the drug for market, about things like chemical formulation, and the size of the pill, based on factors like unit cost, and ease of manufacture that lead to its failure. They had ultimately chosen between the wrong set of options for all the right "business" reasons.

It turned out that their research and development group had two big challenges of communication. First, the scientists were isolated from the audience they were ultimately designing for, in this case patients, which made it difficult to understand their needs. And second the R&D group didn't have a vocabulary with which to communicate internally, and to turn the information they did have into design. We, that is IDEO, were engaged to give them tools to help make better decisions during the development process. To help them better know the patients, understand the impact of different conditions, and to appreciate the challenges of different therapies from the patients perspective.

I was fortunate enough to work closely with a group of scientists, engineers, and managers who were smart enough to understand that without greater empathy for their audience, and a better vocabulary with which to communicate they would continue to base their choices on the wrong options. They needed a way to consider the context of of the therapy application, or risk continuing to select unusual dosing regimens, or ignoring difficult side effects, because their process would not have generated good options that accounted for those problems.

We wound up using traditional mediums of graphic design to create tools that inspire empathy for patients, prompt good questions, and provoke action on the part of scientists in the early stages of developing new therapies. We made a choice to convey patient stories in the patients' own words, as opposed to the typical marketing speak that pervades much of the medical space. Our intent was to use self portraits and documentary photography in order to accurately portray the lives and challenges of patients. But because of the particular constraints and legal requirements for patient confidentiality that govern the pharmaceutical industry, we couldn't use patient photography. It was a real disappointment.

But we were able to communicate our desire and intention for those choices, as well as their intended effect to our partners. Who in turn adopted our rationale and vocabulary as their own for future work. Which was a great outcome.

In the end, we worked on a different aspect of the problem than I would have expected going in. My initial reaction might have been to focus on packaging, positioning, or messaging, but I wound up engaging years ahead of that work. Helping to frame decisions that will eventually frame the treatments. Some of the therapies we considered were as many as ten years away from the market, but our design criteria will hopefully have a big impact on the form they take, and how they address the needs of patients when they do eventually arrive.

So clearly there is opportunity for designers to have influence in situations that aren't directly related to our discipline. It is incredibly valuable to open up the design process to include multiple perspectives, and to engage non-designers in creative conversations. But at the end of the day all of that value will be lost if there isn't someone capable of translating all those conversations into something real. A paragraph is one way to express a concept, but making a thing is a much fuller way to do it. It is important to help clients understand that writing ideas on post-its and brainstorming is great but it is only a portion of the work, all of those ideas will require skilled makers to implement. There is a good chance that the ideation and final implementation parts of the engagement could be separated by a fair amount of time, and the benchmarks of success will be unfamiliar. So having some new ways to measure your own success will become important.

Designers are often motivated by what I'll call ego moments. The pleasure of making something cool and sharing it. Pointing to something on a shelf or on a screen and saying "Look how cool that is, I made that". When you're engaging in problems further up stream those ego moments can be much harder to come by, and it can be a source of frustration. It will also make your portfolio much harder to share, because the bulk of your contribution might not be visual.

For me those measures of success have come from introducing clients to a new vocabulary and hearing them share it with their colleagues. Or developing a set of design criteria with clients and watching as the tools we created together live on within an organization, and influence future decisions. Your personal measure may be something different, but it isn't exactly going to be the same instant gratification that comes from adding a sweet new piece to your portfolio.

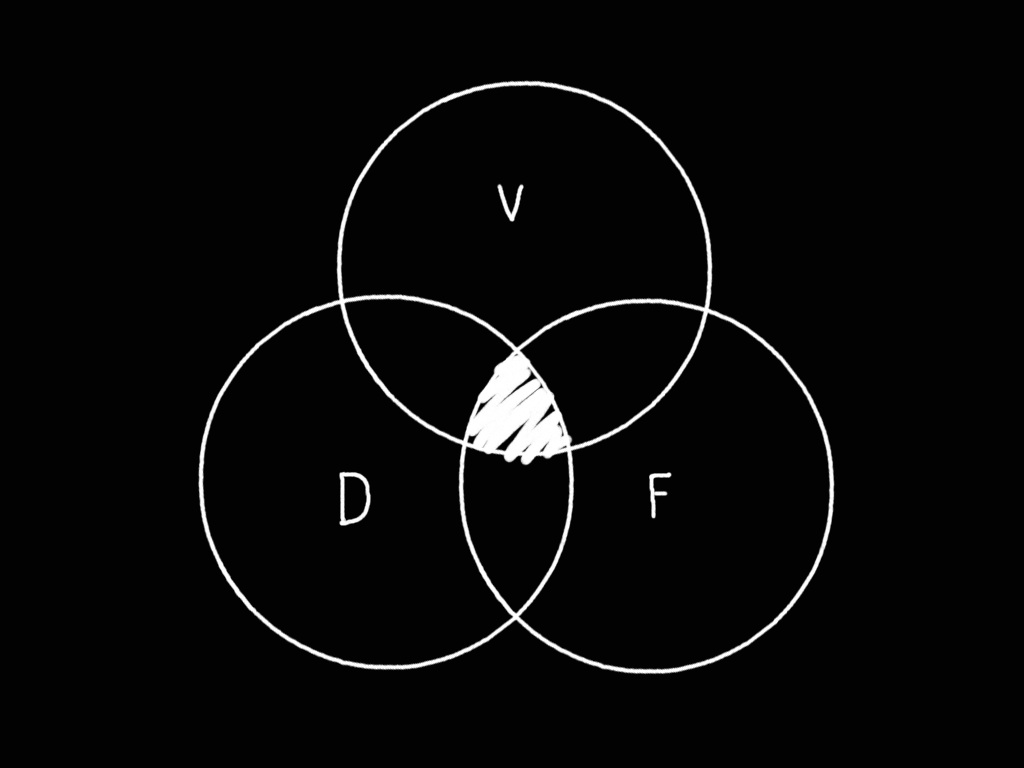

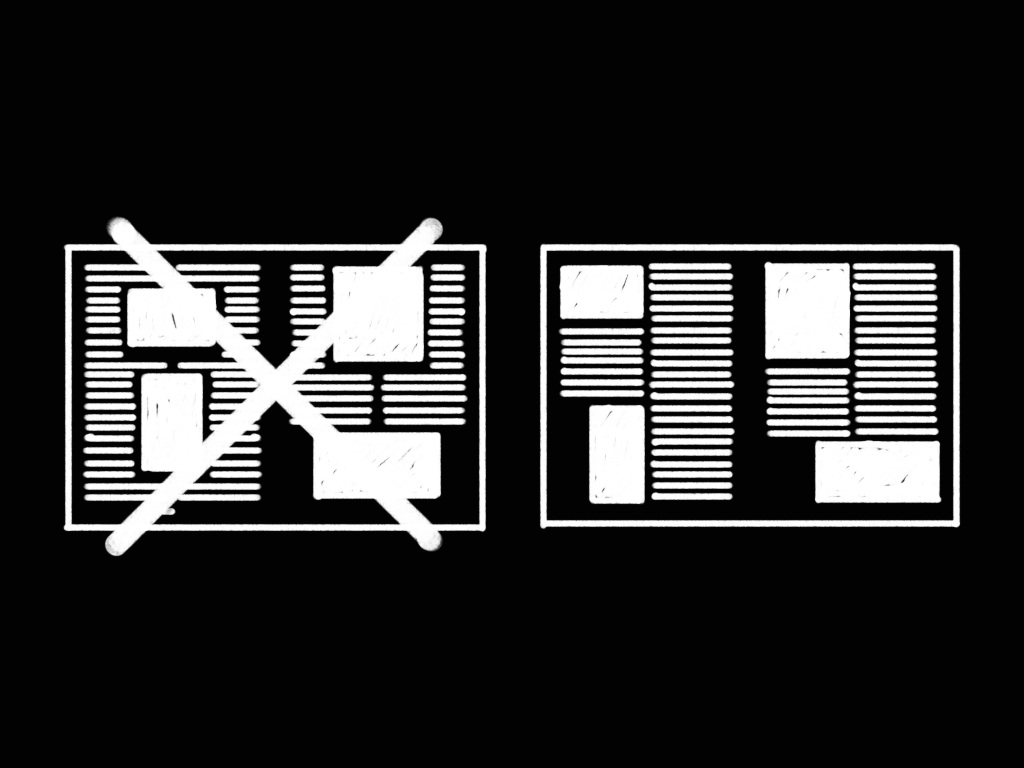

Aside from creating new benchmarks for success it will also be important to figure out how to assess your own particular breadth and depth. One useful way to visualize and account for both breadth and depth is the simple T shape. With the height of the T representing depth in a particular discipline, and the width of the T representing interest or engagement with content not directly associated with that discipline.

There are several important factors to remember: first it is no longer a breadth versus depth conversation, but rather a discussion of breadth and depth simultaneously, so having an extremely narrow or very wide T isn't a great thing. Next is to be honest in assessing the shape of your particular T. The clearer your concept of your individual arrangement of breadth and depth the easier it will be for you to figure out how to engage in a given problem, and admit what you don't know. Knowing your T shape will also help you begin figuring out what you will need to learn, and to select collaborators based on the shape of their T, and to balance or augment each others attributes.

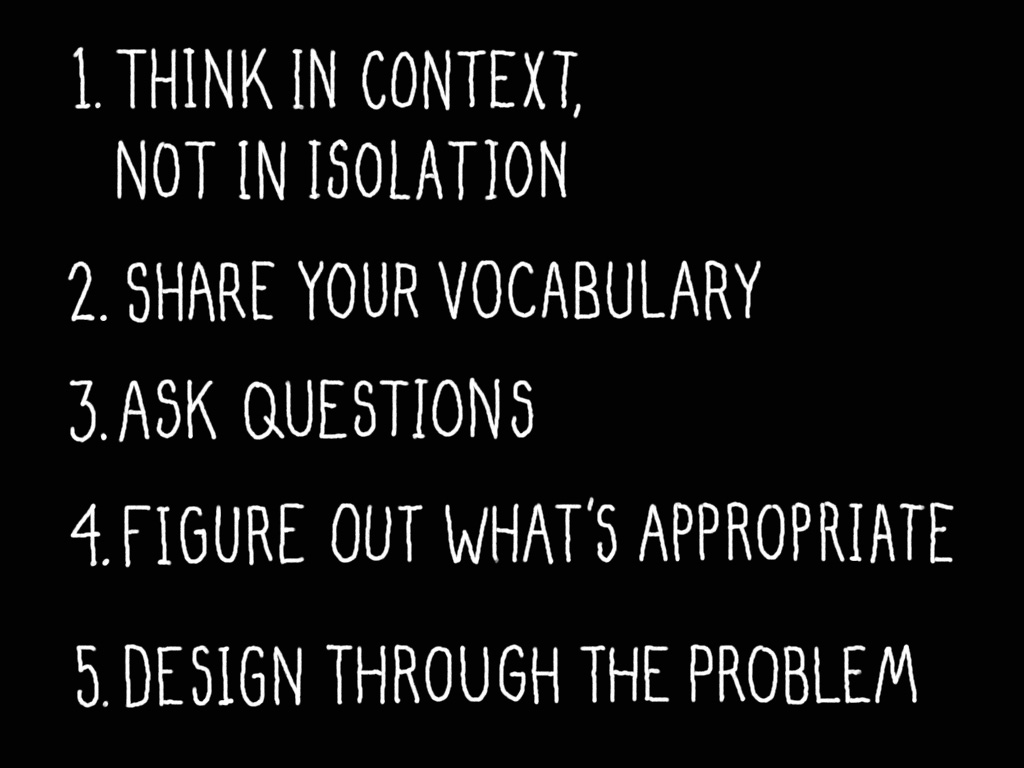

In addition to thinking about the breadth and depth of your T, I thought it would be helpful to think about some guiding principles for designers attempting to engage this way.

1. Think in context, not in isolation

Know how to frame a problem and connect it to a system, whether it is the particular business and capabilities of your client, an unfamiliar culture, new technological considerations, or the specific attributes of a brand.

2. Share your vocabulary.

Help others understand what you are doing. Be open and transparent. Don't use opacity as a way to protect your expertise. Just because someone learns your vocabulary doesn't mean they could do your work themselves.

3. Ask Questions

There is a difference in engaging a problem to discover what to make, and engaging the problem of making a thing. The first has more open questions and the second more specific ones. Learn how to ask both.

4. Figure out what's appropriate.

Most designers are optimists, with a tendency to be perfectionists and an urge to wipe the slate clean. But it's important to figure out if it's appropriate to solve the problem in an ideal way, or if it's appropriate to simply satisfy the brief? Have a clear idea of who's problem you are actually solving.

5. Design through the problem.

Make things as early as you can. Most non-designers have trouble visualizing something new or foreign, and need something to react to even if it's not quite right. Don't just talk about it or write about it. Visualize it. Making it as real as possible will help you figure out what's working and what's not. It will also make your idea more compelling to your client, they will fall back to old habits and solutions if they don't have an example of what else it could be.

In the end I am personally interested in a role for design somewhere between the Decision and the Design Mindsets, basically including a little of both. Many businesses are really good at refining things, and figuring out ways to make more money through incremental changes to a process or product. There may be innovations there, but it won't get you anything new. I don't think the big opportunities will come from exploiting what you already have, but from exploring what you don't know, an activity I believe designers are particularly suited for.

It will require acting as a mediator, and finding ways to connect strategic thinking and the craft of design. With the ultimate goal to participate as designer and creative consultant rather than as an aesthetic service provider. Incorporating the abilities to consider scale, impact, and engaging in context, and of course to make cool things. It is probably going to make both designers and clients really uncomfortable at first. And will require concentrated effort to help both stretch, understand, and feel comfortable in this new relationship to be successful, but those seem like small obstacles to overcome in light of the opportunities if we're willing to try.

Thanks.